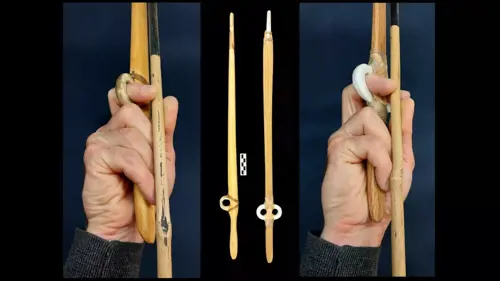

For over 150 years, scientists have been baffled by enigmatic, C-shaped antler carvings dating back to France's Stone Age. However, a recent study may have finally unraveled their purpose. The research involved an innovative experiment using similar crescent-shaped devices to throw dart-like projectiles at archery targets, leading to a breakthrough discovery. The study suggests that these carvings, known as "open rings," were likely finger grips for Paleolithic spear-throwers.

Spear-throwers, also called atlatls, were ancient weapons used to hurl large darts at high speeds. The open rings, made from deer antler, were probably attached to the wooden spear-throwers, which have long since rotted away. The researchers behind the study, Justin Garnett and Frederic Sellet from the University of Kansas, used their findings from the projectile experiments to support their hypothesis. While no Paleolithic atlatl with attached open rings has been found yet, Garnett and Sellet are confident in their conclusions.

The open rings were first discovered in the 1870s at Le Placard Cave in southwestern France, along with subsequent findings of ten more rings in various locations across France. Only one open ring, still attached to the rest of the antler, has been directly dated to approximately 21,000 years ago, belonging to either the Magdalenian or Badegoulian culture.

Previously, archaeologists suggested that these artifacts may have served as ornaments or clothing fasteners. However, Garnett, an experienced spear-thrower maker, recognized their distinct shape resembling finger loops. Drawing on his expertise, he conducted experiments with replicas of the open rings made from cattle bones, elk antler, and 3D-printed plastic, attaching them to replica spear-throwers.

Over the course of a year, Garnett launched darts with the spear-throwers at archery targets, comparing the results to earlier studies that had used animal carcasses. By using targets, he avoided ethical concerns. The experiments confirmed that the open rings functioned effectively as finger loops and may have been more durable than loops made solely from animal hide. The wear patterns on the replicas also resembled those seen on the original open rings.

Experts in Paleolithic hunting, such as Pierre Cattelain from the Free University of Brussels, find the study fascinating. Cattelain had previously proposed in the 1990s that the open rings served as finger loops for spear-throwers, but his idea was not widely accepted at the time.

While this recent study sheds new light on the purpose of the mysterious open rings, it is crucial to approach interpretations of prehistoric artifacts with caution. Nevertheless, the evidence gathered thus far suggests that these 150-year-old enigmas from France's Stone Age were likely functional finger grips for Paleolithic spear-throwers, providing further insights into our ancient ancestors' hunting techniques.

Summary:

- Enigmatic C-shaped antler carvings from France's Stone Age, known as open rings, have puzzled scientists for over 150 years.

- A recent study suggests that these open rings were likely finger grips for Paleolithic spear-throwers.

- Experiments using similar crescent-shaped devices to throw dart-like projectiles at archery targets supported this hypothesis.

- The open rings were made of deer antler and attached to wooden spear-throwers, which have since decayed.

- The study's findings indicate that the open rings functioned well as finger loops and may have been more durable than animal hide loops.

Conclusion:

The 150-year-old mystery surrounding the enigmatic C-shaped antler carvings from France's Stone Age has finally been solved. The recent study provides compelling evidence that these carvings, known as open rings, were likely finger grips for Paleolithic spear-throwers. By conducting experiments with similar devices, researchers demonstrated the functionality of the open rings as finger loops for launching dart-like projectiles. This breakthrough sheds new light on our ancient ancestors' hunting techniques and enhances our understanding of prehistoric cultures. While caution is necessary when interpreting artifacts, the study's findings offer a compelling explanation for the purpose of these intriguing archaeological finds.

Discover More

Most Viewed

Christmas is a season of joy, love, and traditions. And what better way to get into the holiday spirit than through timeless carols? These musical gems have been bringing people together for generations. Here’s our ranked list of the Top 10 Christmas Caro…

Read More